Volunteer Force - Pt. One

When I was trundling down the M1 towards West Sussex I had no idea I would be accompanying Peter, who was turning 91 next month, to the front lines of Ukraine. I had met Charles, Peter's son, a year prior, and our small chat leading to this moment was initiated by the introduction of “Charles goes to Ukraine” at his son’s wedding. At that moment, I did not realise the scope of the de la Fuentes mission.

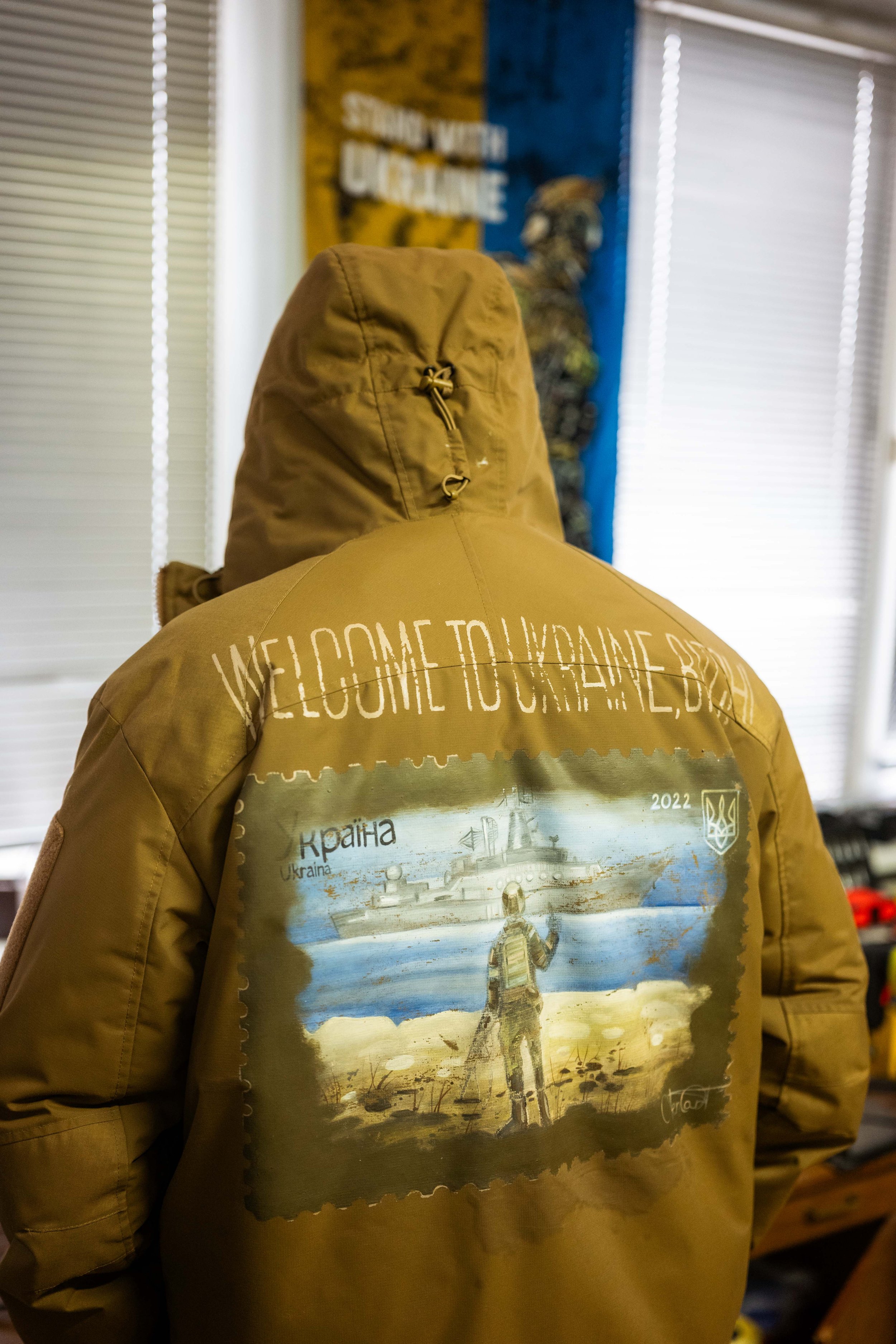

Since the start of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the de la Fuente family have been delivering humanitarian aid to NGOs in Ukraine. This crusade instigated the fostering of a Ukrainian family in the de la Fuente farmhouse, which launched them into a network of civilian volunteers helping the war effort.

It wasn’t driven by activism but by the human need to help others who require it. Peter had the space and the family support to enable this step. When I asked why he replied, “Just human nature, I’ve got the room. Why not? I have family support around, that obviously helps enormously”.

Through local connections in the West Sussex area, Peter and his family were linked up with a Ukrainian family who lived in Hostomel and escaped on the day of the invasion, a place occupied by Russia in the early days of the war and notorious for civilian murders and atrocities.

That first journey to Ukraine emerged directly from hosting the family. Peter admits that before meeting them he “knew nothing about Ukraine really, it’s just a blob on a map”, but the reality of the war quickly became personal. When President Zelensky ruled that “no men under 60 were allowed out”, there was “no question of Teras [the father of the adopted Ukrainian family] coming back here”, and as Kyiv became relatively safer, the family decided to return, because, as Peter put it, “you’ve got teenage kids, they need mummy and daddy, not just mummy or anybody else, they need the family”. So instead, the de la Fuentes took help to them, loading “a car full up with medical” supplies, using hospital connections to access surplus equipment, and taking “30 boxes in the back of the car and went out there”. As Peter says simply, “then it’s grown from there.

I was joining Peter’s 9th trip to Ukraine and final trip of 2025. To fully appreciate the scale of this team’s operations, the frequency of trips must be viewed in the context of the length of each journey. It is 2000 miles each way to Kharkiv from Chichester, a small city situated in the centre of the UK’s south coast. This, including the detours on route to deliver aid, takes 2 weeks at least. It was a mammoth undertaking of sitting in a car seat for up to 9 hours a day for me, let alone for Peter.

Peter’s motivation is rooted as much in memory as in the present. Having “lived through the Second World War”, he remembers Britain as “a small nation in the UK, needed all the help it could get”, reliant on others “at the vital moment when Hitler appeared on the edge of France about to invade”. That experience gives him an instinctive understanding of “the desperate state that they were in”, and echoes through his reflections on Ukraine today. He believes that “we kind of feel almost like our democracy, our freedoms are taken for granted, which is why we don't quite appreciate what Ukraine's going through”, and that witnessing the war first-hand is a reminder that “you don't understand freedom until you lose it”, something that, once gone, “would probably nearly impossible” to recover.

When we arrived at the frontline in our two-vehicle convoy – we were visiting a battalion the de la Fuentes had delivered to before – Peter and his two sons, Charles and David, were met with massive smiles and handshakes. The appreciation was real. Our contact there wanted to show us a new entrenchment they were building 5km from the nearest Russian position. When this was offered to us, with caution due to the threat of drones flying overhead, Peter and Charles leapt at the opportunity, and Peter was the first to get his flak jacket on. Driven by a deep admiration for the resilience and determination of the Ukrainian people, Peter was eager to see first-hand how they continued to fight, build, and endure in the face of constant danger. He did not hesitate to pile down into the bunker, currently under construction. As he put it, “Well, first of all, they are still unbelievably determined and keep going. And you just wonder how, how you wouldn't eventually say, okay, I can't be bothered anymore…what drives them on to do it? And it has to be this business of…experienced the oppressive nature of authoritarianism. And they don't like it. And so they are very determined to stick to what we term as a democratic system.”

Peters sees this effort continuing, even more so now that him and his family have personal ties with those both supporting and fighting in the war effort. “It'd all feel a bit for nothing as well, wouldn't it? Why have all these people died for the freedom of those who still remain, if suddenly, you know, we're bored of it.” Peter is aware that a van and a car going out a few times a year might not change the outcome of the war on their own, but he believes that if everyone does their bit, it will collectively shift the course of events. Beyond the tangible aid, the motivation and appreciation from those they are helping carries immense weight. For Peter and his family, seeing the gratitude and resilience of the Ukrainians they assist reinforces the importance of their ongoing efforts, however small they may seem in the grand scheme.

For Peter, the challenge has always been conveying the reality of Ukraine to those so far removed from it. He laments, “For us, the difficulty is definitely getting people to understand how desperate the situation is, because it's such a long way away.” The relentlessness of life under constant threat - sleep disrupted by air raids, the effort to appear normal amid devastation - is almost impossible to grasp without seeing it first-hand. “You can't understand that…until you go there and…you’ve got some idea of the fear, how they make a huge effort to be normal, but it's not normal.” I had that fear, the cold run of blood when we entered drone range, the nightmarish dreams of drones as they fly overhead at night. I was only visiting, I couldn’t imagine what it would be like to live there.

At the time of writing this, the Ukrainian estimates of Russian casualties lie at over 1.2 million, and the Ukrainian casualty count remains vague. There is no end in sight with peace talks between Zelenski and Putin proving endless due to Putin’s impossible demands. So the fight for Ukraine’s sovereignty goes on, and therefore, Peter and his family's aid runs must also continue. Peter ended our chat with “It's been going on for nearly four years, and how do you keep it up day after day after day?”