The struggle to come to terms with the emergence of COVID-19 out of China was real. The world had faced the possibility of pandemics before—swine flu, bird flu, and Ebola. All of these threats diminished, solidifying the belief that global outbreaks of disease were an impossibility, even in my mind. I would tell my peers, friends, and family, “Of course there will be a disease that will hit us hard; we have a hugely connected planet with pathogens constantly evolving. We are only a few mutations away from a lethal pandemic.” Yet, I didn't truly believe it would happen. Inevitability battled inside my head against experience, or more accurately, naivety—thinking it wouldn't happen in my lifetime.

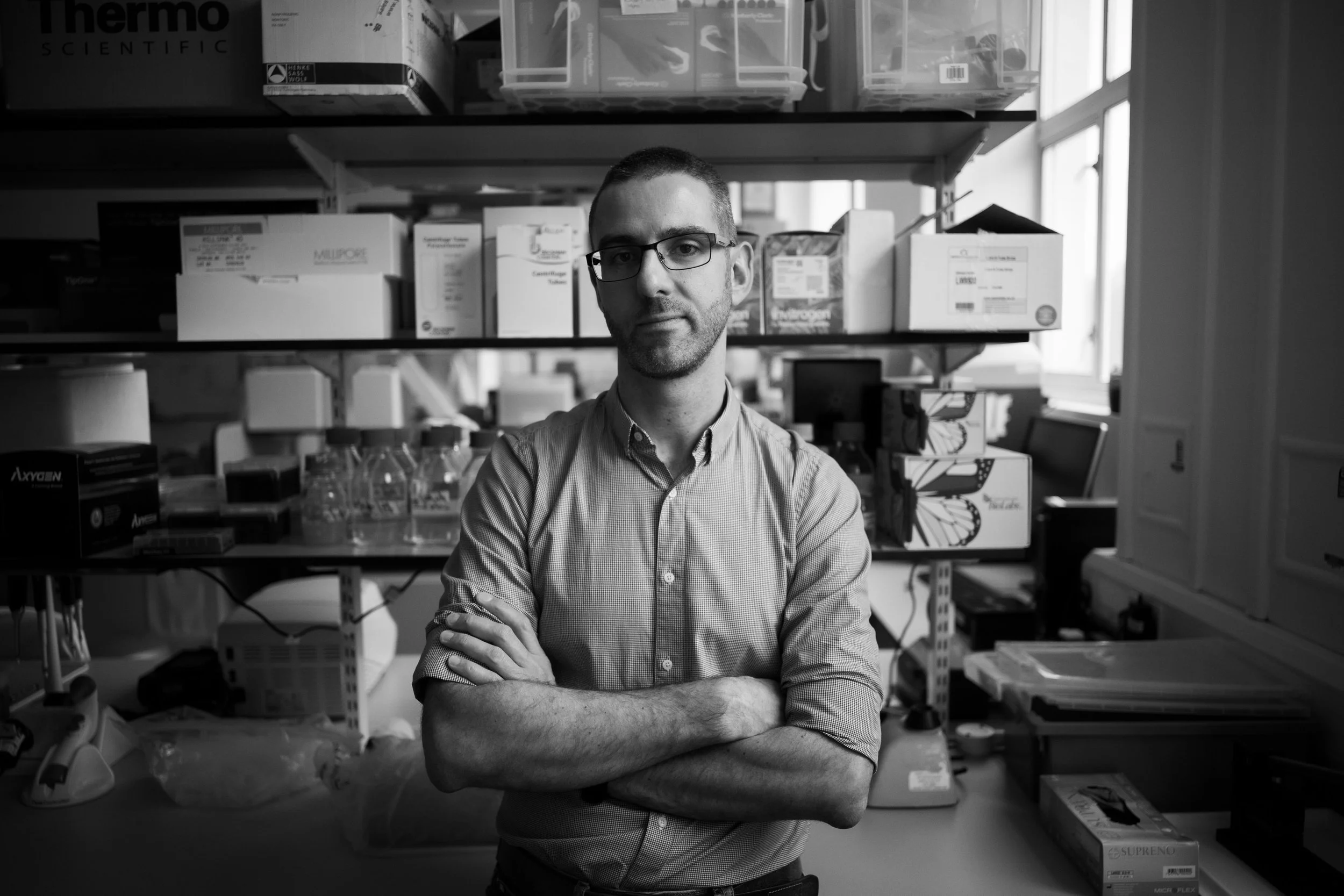

Yet, the pandemic did happen and continued to unfold. A vaccine was developed and introduced at lightning speed, with the first administration to 90-year-old Margaret Keenan in the UK by nurse May Parsons. This was phenomenal. It was the first implementation of an mRNA vaccine in humans, something that hadn’t been achieved before for other diseases. As an immunologist and PhD student, this is the sort of thing that excites me, but I understand these things.

For most people in the UK, it was the first time they had heard of RNA, let alone mRNA. What is it? How did it get approved so quickly? What are the long-term effects? Even worse, this vaccine induces the killing and destruction of your own cells? Then the rumors started: infertility, DNA alteration, microchips for tracking, viral shedding, lack of safety, blood clots, and immune cells targeting healthy cells. Some of these could easily be dismissed with a little common sense, while others even I and some of my peers struggled with in the early days.

The vaccine had been authorized quickly, and we didn’t know the long-term effects of this type of vaccine. We had never utilized this type before. It seems the vaccine did have some adverse effects, yet it was safer than getting the virus, at least for most. We were comparing all these unknowns of a vaccine against some knowns and many unknowns of having COVID-19.

This put me in a tricky situation. I was an 'expert' in the eyes of laypeople, but I didn't know everything, or much at all. People were asking me questions on a topic that no one was a real expert on yet. How do I advise my family and the people I care about on a topic I’m as lost on as they are? I was on the fence as they were in the early days, but I had to trust science.

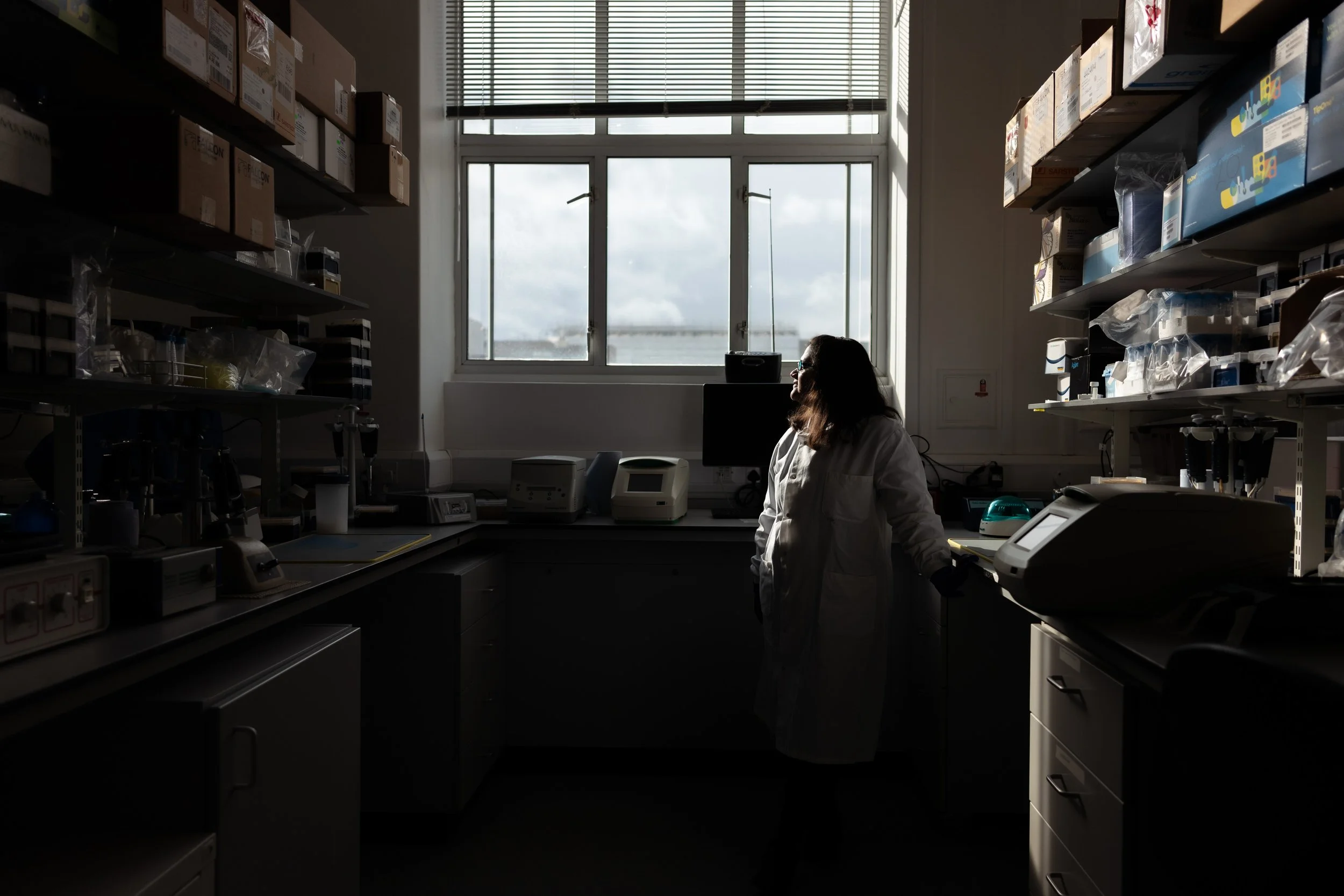

In this series of images, I set out to explore the other side of the fence—those individuals set on not accepting the vaccine and the restrictions implemented by our government. I visited protests, entered debates at Speakers' Corner, and chatted with individuals to gain an understanding of where this refusal came from. I found it stemmed from distrust in our leaders, fear of the unknown, putting two and two together and making three, or protesting the forced implementation of the vaccine and the restrictions. Some of these I had no defense for, and to some, I said you have to just trust the little science we have. I hope you enjoy the images; it was an enlightening process taking them.